The Root

Image of the Week: A painted vase raises a question: Why did the Greeks choose to hide the mythological figure’s true origins?

BY: IMAGE OF THE BLACK IN WESTERN ART ARCHIVE

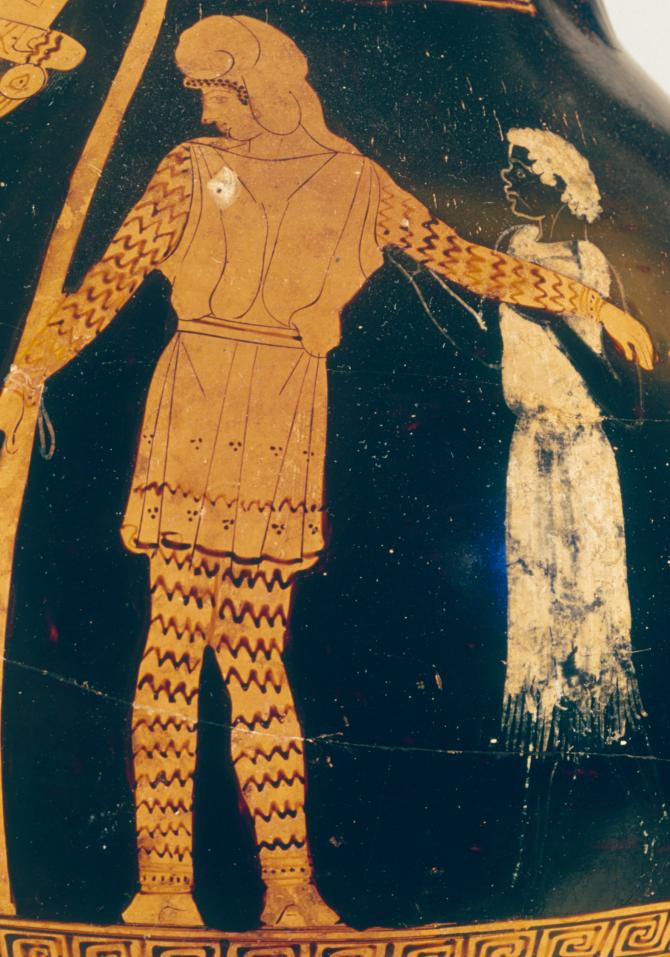

The Niobid Painter, Sacrifice of Andromeda. Red-figure pelike, about 460 B.C.MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, BOSTON

his image is part of a weekly series that The Root is presenting in conjunction with theImage of the Black in Western Art Archive at Harvard University’s W.E.B. Du Bois Research Institute, part of the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research.

One of the most profound qualities of the classical Greek mind has to do with its capacity to interpret human destiny on a cosmic scale. A particularly affecting example is the story ofAndromeda, the daughter of the king and queen of Ethiopia. Like her parents and her lover Perseus, Andromeda was ultimately placed in the heavens by fate, metamorphosed as the constellation bearing her name.

The legend of Andromeda constantly migrates in its telling, always keeping pace with the vibrant, ever-changing perception of the world and its inhabitants by the ancient world. In this evocative example of Greek vase painting, the clear signs of her African origin are tempered with a seeming reluctance to accept the heroine herself as black. Though the reasons for this are not entirely clear, the treatment of Andromeda’s story provides valuable insight into the presentation of race in legend and art, and perhaps in actual life as well.

This particular form of vase is the pelike, a graceful vessel used by the ancient Greeks for the storage of oil and wine. It seems to have originated in the major pottery-producing center of Athens during the late sixth century B.C. Its decoration often depicts the feminine themes of wedding preparations or domestic activities such as the bath or dressing. This example, painted in the middle of the fifth century B.C., is no exception to this practice, for Andromeda was to be married at the time of her mother’s offense.

It was produced in the studio of the Niobid Painter, one of many vase painters whose actual name has not come down to us. Instead his work bears the provisional name derived from the subject of his key work, a vase depicting the myth of Niobe and her children. The Niobid Painter is best-known for his subtle suggestion of depth, incisive linear description and graceful rendering of the human figure.

Here, on the left, Andromeda has been tied to a stake in preparation for sacrifice by her father Cepheus. His wife, Cassiopeia, had insulted the god Poseidon by claiming to possess greater beauty than the female sea nymphs who cavorted through the waves of his kingdom. As punishment, the couple was forced to sacrifice their daughter Andromeda to the god of the sea by offering her to a hideous sea monster. She is saved at the last moment by the hero Perseus, who turns the creature into stone.

A youthful black servant holds Andromeda’s left arm and gazes up at her in an apparent gesture of sympathy. The exposed skin of the servant, including the face, is actually depicted as black, a fact that would not seem surprising except for its apparently unique occurrence here. This vase is of the red-figure type, in which all figures, including dark-complexioned personages, are usually rendered in the natural reddish hue of the clay.

In this case, however, the Niobid Painter has taken the opposite tack, adopting the brilliant but apparently unique expedient of using the black area of the vase to represent the skin color of the servant. Instead of tracing the interior details of the figure with dark paint, like that of Andromeda, he instead applied white paint to define the servant’s contours. In effect, he creates a figure from the dark void of the vase’s surface with the sparest of means.

The profile features of Andromeda herself do not seem classically Greek. Her long nose and curving face may be intended to represent a woman of the Near East, the usually understood locale of the story before its transfer in the Greek imagination to Ethiopia. The style of her clothing clearly reinforces this interpretation. Her ensemble is assembled from diverse elements of exotic Asian dress as these appear in Greek art.

The locale of Andromeda’s sacrifice on the vase is not explicitly stated, but the presence of a black serving figure by the girl’s side establishes the setting as Ethiopia. When this vase was painted, the concept of Ethiopia had been narrowed by historians, such as the contemporary scholar Herodotus, to the region in Africa bordering the modern areas of southern Egypt and northern Sudan. This land of the “burned faces,” as the term Aethiopes was taken to mean, was thus found in the semiarid zone on either side of the first cataract of the Nile.

The mythographer Pherecydes, who lived in the sixth century B.C., seems to have been the first to locate the Andromeda story in Ethiopia. The popular works of this compiler of myth and legend eventually affected the artistic consciousness of Athens. The black land of Ethiopia is the locale for the story in two plays written by the great classical playwrights Sophocles and Euripides, as well as for a considerable number of surviving vase paintings. Yet throughout the history of ancient art, Andromeda remained white in her transposed homeland.

In the literary imagination, however, the heroine’s complexion was already changing. The Roman poet Ovid clearly refers to her as dark-skinned more than once. During the early Renaissance her ethnic identity continued in this direction. The process began with the Italian humanist author Petrarch in the 14th century who, perhaps inspired by Ovid, explicitly described her as black. Three centuries later the Dutch artist Abraham van Diepenbeeck finally gave visual form to this new interpretive turn. The dark body of Andromeda is shown chained to the rock in his illustration of her intended sacrifice in The Temple of the Muses, an erudite treatment of classical subjects composed by the French scholar Michel de Marolles.

To the Niobid Painter, however, the ethnicity of myth remained conditioned by the nearer and more familiar reaches of the world known to the Greeks. In the final analysis, it was probably the inherent desire for cultural continuity, rather than any more modern type of racial prejudice, that for the Hellenic imagination kept Andromeda a whitened exemplar of beauty and cosmic destiny.

The Image of the Black in Western Art Archive resides at Harvard University’s W.E.B. Du Bois Research Institute, part of the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research. The founding director of the Hutchins Center is Henry Louis Gates Jr., who is also The Root’s editor-in-chief. The archive and Harvard University Press collaborated to create The Image of the Black in Western Art book series, eight volumes of which were edited by Gates and David Bindman and published by Harvard University Press. Text for each Image of the Week is written by Sheldon Cheek.

Source : theroot.com